Diagnosing and treating interstitial cystitis

Also called painful bladder syndrome, this frustrating disorder disproportionately affects women.

Interstitial cystitis is a chronic bladder condition that causes recurring bouts of pain and pressure in the bladder and pelvic area, often accompanied by an urgent and frequent need to urinate — sometimes as often as 40, 50, or 60 times a day, around the clock. Discomfort associated with interstitial cystitis can be so excruciating that, according to surveys, only about half of people with the disorder work full-time. Because symptoms are so variable, experts today describe interstitial cystitis as a member of a group of disorders collectively referred to as interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. (In this article, we'll call it interstitial cystitis, or IC.)

Among the one to two million Americans with IC, women outnumber men by as much as eight to one, and most are diagnosed in their early 40s. Several other disorders are associated with IC, including allergies, migraine, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia (a condition causing muscle pain), chronic fatigue syndrome, and vulvodynia (pain or burning in the vulvar area that isn't caused by infection or skin disease).

There's no cure for IC, but many treatments offer some relief, either singly or in combination. Figuring out what works can be hit-or-miss; there's no way to predict who will respond best to which treatment. Fortunately, increasing awareness and greater understanding of this complex disorder are helping to speed diagnosis and encourage research. In March 2011, the American Urological Association (AUA) issued its first set of guidelines for the diagnosis and management of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. (A summary was published in the June 2011Journal of Urology; the complete guidelines are available here:www.health.harvard.edu/ic_guidelines.) Also, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (a federal research group that reviews what does and doesn't work in health care) is preparing a report on the effectiveness of treatments for chronic pelvic pain in women, including IC; the final report is expected in late 2011, but a draft is available here: www.health.harvard.edu/ic_report.

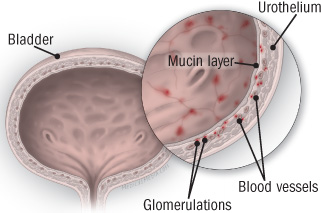

Glomerulations and interstitial cystitis A defect in the layer of mucus (mucin layer) that protects the cells lining the bladder (the urothelium) may permit toxic substances from urine to seep through and inflame tissues. Irritated blood vessels produce tiny areas of bleeding in the bladder lining called glomerulations. Most people with interstitial cystitis have glomerulations. |

Possible causes

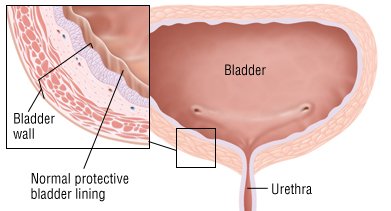

No one knows the exact cause of IC; more than one mechanism is probably involved. Biopsies of the bladder wall in people with IC indicate various abnormalities, but it's not clear whether these are the cause of the condition or the result of some other underlying process. Some research has focused on defects in the glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer, part of the layer of mucus that lines and protects the bladder. Defects in the GAG layer may allow toxins in the urine to leak through and damage underlying nerve and muscle tissues; this in turn may trigger pain and hypersensitivity.

Another line of research centers on antiproliferative factor (APF), a substance that's found only in the urine of people with IC. APF appears to block the normal growth of cells that line the bladder and may hinder the healing process that follows any damage or irritation to bladder tissues. Scientists seeking a diagnostic test for IC are considering APF as a possible biomarker.

There are several other theories about the cause of IC. It may be an infection with an unknown agent, such as a virus. Or it may be an autoimmune disorder set in motion by a bladder infection. It's possible that mast cells normally involved in allergic responses are releasing histamine into the bladder. Another idea is that sensory nerves in the bladder somehow "turn on" and spur the release of substances that contribute to symptoms. Because interstitial cystitis is mainly a woman's disease, many researchers think that hormones play a role.

Variable symptoms

The onset of IC is usually gradual, with bladder pain and urinary urgency and frequency developing over a period of months. The course of the disorder and its symptoms can vary greatly from woman to woman and even in the same woman. Symptoms may change from day to day or week to week, or they may remain constant for months or years and then go away, only to return several months later. Pain ranges from dull and achy to acute and stabbing; discomfort while urinating fluctuates from mild stinging to burning. But virtually everyone with IC has pain associated with bladder filling and emptying. Some women with IC have a constant need to urinate, because urinating helps relieve the pain.

In women who also have chronic abdominal or pelvic pain from other causes, such as irritable bowel syndrome or endometriosis, IC may flare up when those symptoms are at their worst. Sexual intercourse can trigger pain lasting several days, and symptoms may worsen with menstruation. On the other hand, some women experience complete relief during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Some find that their symptoms are worse after consuming certain foods or drinks, including strawberries, oranges, tomatoes, chocolate, spices, caffeine, alcohol, and beverages that acidify the urine, such as cranberry juice.

Diagnosis of exclusion

IC is not a urinary tract infection, and it can't be identified by a simple urinalysis or urine culture. Rather, it's a diagnosis of exclusion, which means that it's diagnosed only after a number of other conditions have been ruled out. A clinician — usually a urologist or a gynecologist — will first take a thorough history, then conduct a physical exam (including a pelvic exam, if it's not too uncomfortable) and perform tests for infection, bladder stones, bladder cancer, kidney disease, multiple sclerosis, endometriosis, sexually transmitted diseases, and other disorders. The AUA guidelines also recommend an early assessment of pain, urinary frequency, and urine volume, to help evaluate the effectiveness of later treatments.

If a diagnosis is uncertain or there are symptoms (such as blood in the urine) that suggest other problems, the next step is usually cystoscopy, which involves inserting a fiber-optic tube through the urethra to look at the bladder wall. During the procedure, a tissue sample may be taken to rule out bladder cancer. Some clinicians favor hydrodistention under local or regional anesthesia, which involves filling the bladder during cystoscopy with a liquid that stretches it, providing a closer view of the bladder wall. However, AUA guidelines do not recommend hydrodistention for either diagnosis or treatment. In people with IC, glomerulations — tiny pinpoint spots of blood — are usually visible on the bladder wall during cystoscopy with hydrodistention, but these lesions are often seen within the normal bladder as well.

One finding from cystoscopy that can help in making an IC diagnosis is the presence of reddened patches or lesions called Hunner's ulcers, which can stiffen tissue and cause reduced bladder capacity. However, Hunner's ulcers, which occur in 10% to 15% of cases, aren't required to make an IC diagnosis.

The potassium sensitivity test, which involves instilling potassium chloride into the bladder to see if it triggers pain, has been proposed for use in diagnosing IC, but it's not conclusive and the AUA does not recommend it for routine use.

Originally Published On:http://www.health.harvard.edu/

Post a Comment